Disclaimer—This article surveys a great deal of material, and there will be many topics I simply am not be able to cover in it. Apologies in advance if I miss your favorite vamp…you can rebut me on the discussion boards.

PART ONE

Basil Copper, writing in 1973, lamented not very prophetically that the difficulty with the vampire story was “investing old themes with new life” (109).

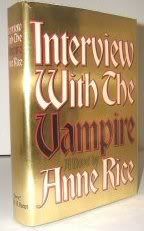

Three years later, in 1976, Anne Rice came on the vampire scene with Interview with the Vampire, which became a runaway bestseller.

Nina Auerbach, in her insightful 1995 study Our Vampires, Ourselves, closes by foreseeing, if not the death of the vampire, the end of the vampire cycle of the 1970’s and 1980s (192). She suggested that vampirism was “wearing down,” and the vampire was in need of a “long restorative sleep.” In truth, what we have seen over the past thirteen years, contrary to this prediction, is that the vampire theme was only gaining strength throughout the 1990s, and continues to be an oddly vital force in popular culture.

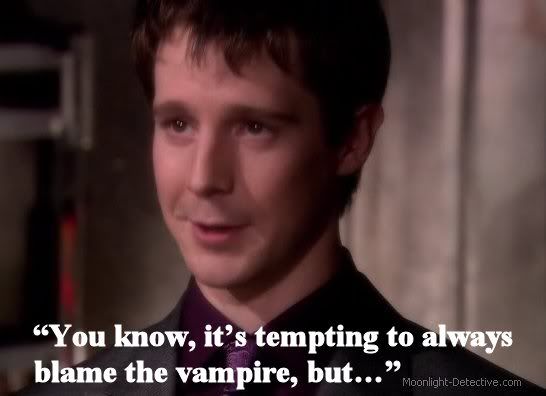

A few examples of this—over three seasons from 1992-1996, Forever Knight brought a tormented, sympathetic vampire to television.

IMDB lists almost 322 films, tv series and video games with a keyword of “vampire” between 2000 and the present.

So I think we can safely say that the vampire is secure in his hold on the imagination of the public. Why is that? Why should the unhuman figure of the vampire continue to hold sway?

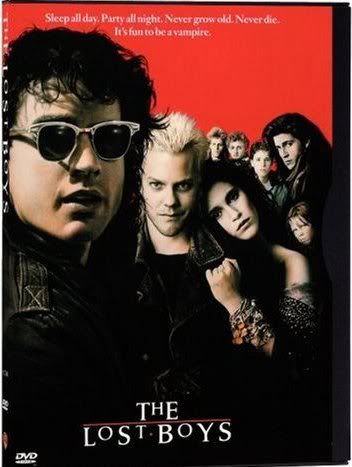

There are probably many reasons. For one, our fictional vampires are cool. They tend to be beautiful, hip, eternally young, often wealthy, and sexually irresistible. The tag line for the 1987 movie, The Lost Boys, put it succinctly: “Sleep all day. Party all night. Never grow old. Never die. It's fun to be a vampire.”

Say you’re writing a vampire story. You need your vampire to fly? Or not to fly? Sure, why not? He needs to be a hero? Fine. The embodiment of all that is evil? That’s all right, too. Whatever serves the purposes of the story.

The reason that Copper thought that the vampire was old hat in 1973 was that he was not seeing the innate flexibility of the creature. Like Cleopatra, “age cannot wither [him], nor custom stale, [his] infinite variety.”

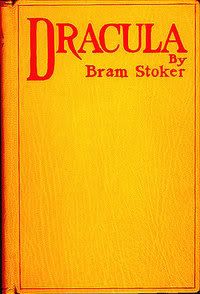

From the beginning, authors of vampire tales have taken the characteristics of the folkloric vampire, and changed and honed these as they needed to make the vampire a better villain, or a better hero, or whatever was necessary at the time.

To explore this idea, it may be useful to look--very briefly--at the attributes of the traditional vampire of legend, and also at the history and characteristics of the vampire as it has evolved in popular narrative.

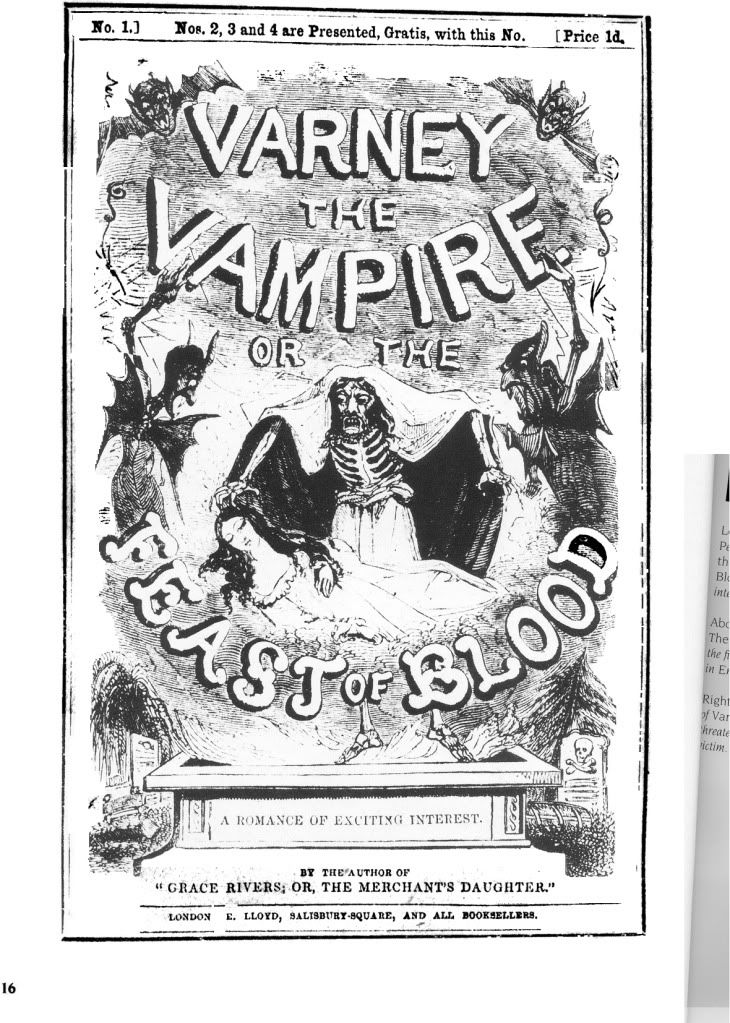

While the vampire as a folkloric concept has far older roots, it bears little resemblance to its literary cousin.

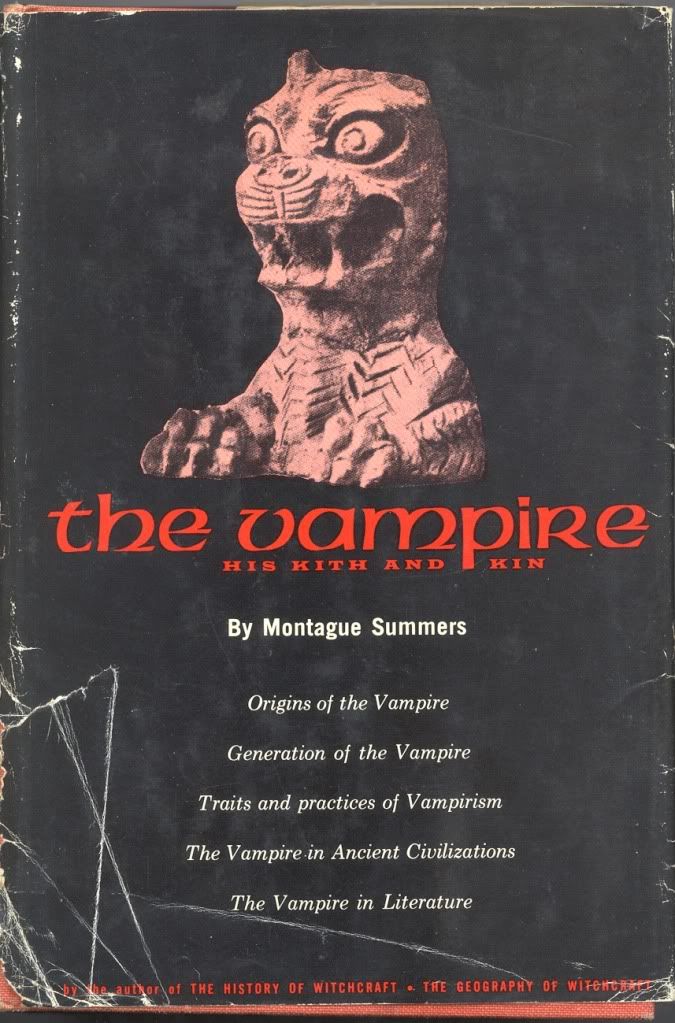

Over the decades, there have been several excellent and in-depth studies of the folklore of the vampire. Montague Summers led the way with his 1928 volume The Vampire: His Kith and Kin.

This rather strange work pulls together vampire folklore from around the world, and finds vampire motifs dating back to Babylonian times.

A more recent study is Paul Barber’s excellent Vampires, Burial and Death (1988),

Let’s look at a short South Russian folktale, as related by Barber:

Now, what are some of the characteristics illustrated here?An old man dies and they buried him. But a day later a healthy youngster died, then again a young innkeeper, and so each day another person died in the village. Finally the only son of a rich peasant died. The peasant could not get over this and went to the priest and told him that someone was eating the people of the village, and that it was certainly the old peasant who had died first. They must dig him up and render him harmless. The priest allowed this. Now the peasant went with three others to the widow of the vampire and said, “Come along, little mother, because we’re off to dig up the old man.” They took a large piece of cloth from her and went with her to the churchyard. They dug up the grave and behold! The vampire sat there, supported on his hands, with a blood-red face, for he had already sucked out a great deal of blood from the people. When the wife saw that, she spat out, “You are to disappear; don’t get up again and don’t move!” Then they pulled him out of the grave, cut him into pieces and tied him in the cloth. Then they threw him onto a thorn bush, set this on fire, and burned the vampire. Hereupon a strong wind arose and blew after them, howling, all the way to the village. (67-68)

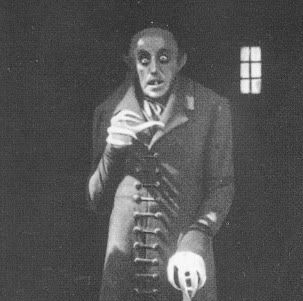

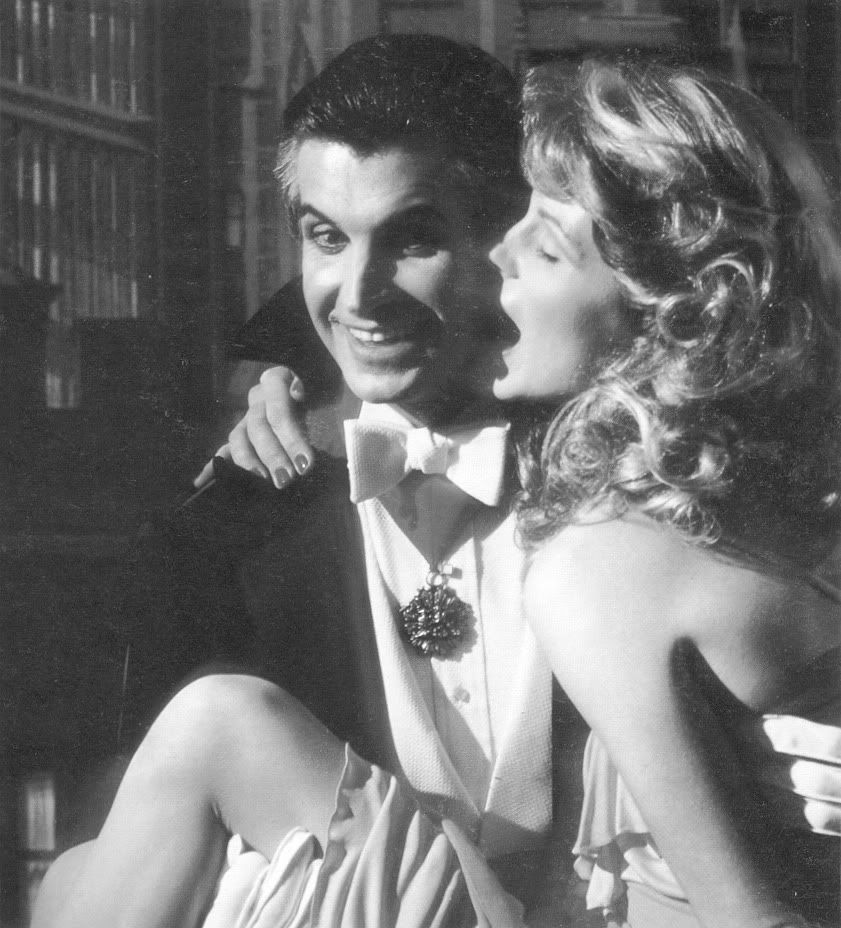

In this traditional tale, as others, the vampire is “undead,” certainly, and prone to rise mysteriously from his grave and suck the blood of innocents; however, we do not see many of the accoutrements of popular fiction and film. This is a peasant, buried perfectly normally in hallowed ground. He is not some exotic nobleman in evening dress making small talk at cocktail parties and seducing nubile young females. The intrepid vampire hunters of fiction are replaced with a couple of locals, laying the revenant with brutal practicality by destroying his corpse. There are no epic battles, no stakes through the heart, no crosses and holy water.

This story, as most of the folkloric stories of vampires, more closely resembles the standard zombie-movie plot. The walking dead man is given no personality, no cognition, just a mindless ravening hunger that is taken out on those who knew him before death. This is not to say that every folkloric vampire tale is so simple, but the focus of most rests with the elaborate ways by which vampire graves may be found, the methods for recognizing the vampire in his coffin, and the various gruesome ways of both dispatching the vampire and making certain he will not rise again.

As J. Gordon Melton states in The Vampire Book: “By the end of the nineteenth century and through the twentieth century, using a definition of the vampire drawn from European folklore and mythology, ethnographers and anthropologists began to recognize the existence of analogous beings in the folklore and mythology of other cultures around the world. While these entities from Asian, African and other cultures rarely conformed entirely to the Eastern European vampire, they shared significant characteristics and could rightly be termed vampires or at least vampirelike entities.” (94)

Obviously, the world-wide phenomenon of vampires or vampire-like beings in folk-lore means that there are many cultural differences in the reported causes of vampirism, as well as the strengths and vulnerabilities of the undead. On the other hand, what vampires share from culture to culture (indeed what causes these beings from disparate cultural traditions to be similarly labeled as vampires) are the basic characteristics of being 1) dead humans that have returned from the grave and 2) that they attack and suck blood from the living as a means of sustenance.

Some of these folkloric elements have been carried over into popular fiction, but since the majority of contemporary vampire novels, etc. focus more on the subjective experience of being a vampire, and less on the vampire hunter, they are currently less central to the vampire tale. If anything, fictional vampires are even harder to kill than their folkloric counterparts, especially since in addition to unnatural strength and reduced physical vulnerability, fictional vampires are usually gifted with high intelligence and cunning, and a long history of evading destruction by enthusiastic but unskilled amateur vampire slayers. But more about that later.

v

v