Thanks for the article, maggatha. Quite a bit to chew on, pardon the pun, but I found myself agreeing with the author of the article in that a work of fiction can be over-analysed.

In such a context, we do not need to look for political meaning in Dracula’s transactions with women. The meaning is forbidden sex—its menace and its allure. The baring of the woman’s flesh, her leaning back, the penetration: reading of these matters, does one think about immigration?

I don't disagree that there are other subtexts in 'Dracula', but one can get carried away.

So why are vampires still thrilling? The quote above is in part an answer. Sex sells. The hard part is making it thrilling from a literary point of view for today's audience.

As indicated in the article, Stoker's original audience was totally different than today's audience. Sex was whispered about, dalliances and affairs weren't flaunted, not if you valued your reputation. As we entered the 20th century, little had changed from the perspective of the audience who viewed the 1931 'Dracula'. Bela Lugosi's interpretation of the Count tended to highlight the attractive and downplay the repulsive. We see nothing of the gargoyle like 'Nosferatu', but rather a refined, elegant, mysterious count from a foreign country. No wonder the ladies swooned.

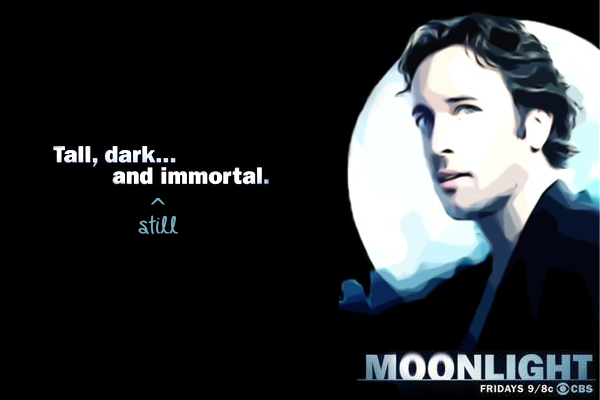

In the interim, we've had the sexual revolution in literature and on-screen. Not much, if anything, has been left to the imagination. The subsequent interpretations of vampires in the last 30 or so years have kept much of what makes the vampire attractive, but added a sympathetic dimension as well. Case in point, Mick St. John and Angel - both physically attractive men who have 'regrets' they're trying to atone for. We've made the vampire more acceptable and given him something he never had before - the hope of salvation.

Modern interpretations of the vampire lore tend to fall into one of two categories - those that harken back to Stoker's view of a creature superficially attractive and mysterious, yet basically reprehensible, relying on the life's blood of others to survive. Take Anne Rice's Lestat. Over the course of her works, he outwardly transforms himself to fit the era he finds himself in, but within, is still Lestat, a vampire who will do what it takes to survive. By the time we get to 'Memnoch, the Devil', though, even Lestat begins to question himself and his path.

The author cites 'Twilight' and 'Buffy' as examples of the second category which tends to highlight the attractive and mysterious, while downplaying the repulsive. Why? Because the target audience has become more diversified, in short, younger. Pre-teen and teenage girls have joined the ranks of the swooning Victorian ladies who have fallen under the vampire's spell.

As for the final quote in the article, 'Moonlight' didn't come to mind, rather 'Angel' did.